Unpredictable Patterns #107: The European Application Advantage Hypothesis

Can Europe win on applications of AI? What does it take?

Dear reader,

This week we dig into the interesting emerging shift in European geopolitical technology competition (that is a mouthful!). From thinking that we need to compete on the dimension where the US is the strongest, some now argue that maybe we should find another way forward - and look at how we compete in use and application of new technology - but what does that really mean? This is what I want to start looking at in this week’s note.

As always I want your thoughts and comments, so do let me know what you think. Last week’s rather abstract note on the end of writing and reading generated some good insights and discussions - not least the irony of sending people 4000 words noting that they would soon not be reading - and one of the great take aways for me was that there are different kinds of reading. While book reading and newspaper paper reading might be slowing down, we now see new kinds of reading, not least bot-assisted reading, where a podcast or conversation with a text replaces traditional linear reading. Such practices still depend on the text though! More on that in a future note!

Finding the key to European competitiveness

In competition it matters which dimension of competition you choose. The simple ones are things like price and quality, but when it comes to geopolitical competition on technology, other dimensions apply - not least the technology / application dimension. At least that is what a lot of European commentators have been arguing. Here is Swedish super-entrepreneur Niklas Zennström, in the Financial Times earlier this year:1

“Think what happened with mobile and the cloud: there are a few cloud providers in the world, they enable thousands and thousands of businesses,” he said in an interview. “It’s not like everyone needs to be a large language model . . . You can create value as an application provider.”

Zennström is not alone. Ursula von der Leyen has suggested the same, and was quoted in Davos, already in 2024, as saying:2

"Our future competitiveness depends on AI adoption in our daily businesses, and Europe must up its game and show the way to responsible use of AI. That is AI that enhances human capabilities, improves productivity and serves society."

But what does this really mean? Focusing on the adoption and the application of a technology rather than the development of it sounds easy enough - but how do you do that? This is worth looking more closely at, especially as it has become a central tenet of the new and emerging approach to geopolitical technology competition that Europe is taking.

From technology competition to a new hypothesis

Europe has, albeit slowly, moved from a stance that essentially tried to compete primarily on the technology dimension to one that is now searching for competitive strategies.

The Quaero project serves as a compelling example of Europe's historical approach to technological competition, highlighting a tendency to focus on fundamental technologies rather than applications that build new use cases.

Launched in 2005 through a joint announcement by French President Jacques Chirac and German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, Quaero represented what has to be said to be an ambitious attempt at the time to develop a European alternative to American search engines.

Rather than focusing on creating a consumer-facing product that could directly compete with Google or Yahoo, the project emphasized developing foundational technologies for multimedia content processing. This approach reflected a distinctly European strategy: prioritizing fundamental research and technological capabilities over immediate commercial applications.

The project's technical scope was notably broad and research-oriented. Instead of building a straightforward search engine, Quaero aimed to create sophisticated tools for indexing and managing multimedia content across multiple languages, including advanced capabilities for searching images, audio, and video. This comprehensive approach brought together major industrial players like France Télécom and Thomson, alongside a multitude of research institutions such as INRIA and the University of Karlsruhe, creating a consortium that embodied the European model of public-private collaboration in foundational technological development.

However, the project's trajectory revealed the limitations of this approach. By December 2006, fundamental differences emerged between the French and German partners regarding project objectives. These differences were so significant that Germany withdrew to pursue Theseus, its own initiative focused on semantic web technologies.3 This split highlighted a recurring challenge in European technological initiatives: balancing different national priorities and approaches while maintaining project coherence.

Despite receiving €99 million in European Commission funding in 2008, Quaero struggled to translate its research focus into competitive advantages in the real-world search engine market. The project's conclusion in December 2013 marked not just the end of a specific initiative, but illustrated broader challenges in European technology policy: a constant and insistent tendency to try to compete on the technology dimension, and in particular on technologies where the US already were leading.

This is the approach that more and more people now think that Europe should abandon, but what should we bet on instead? What is the new hypothesis here?

The application advantage hypothesis

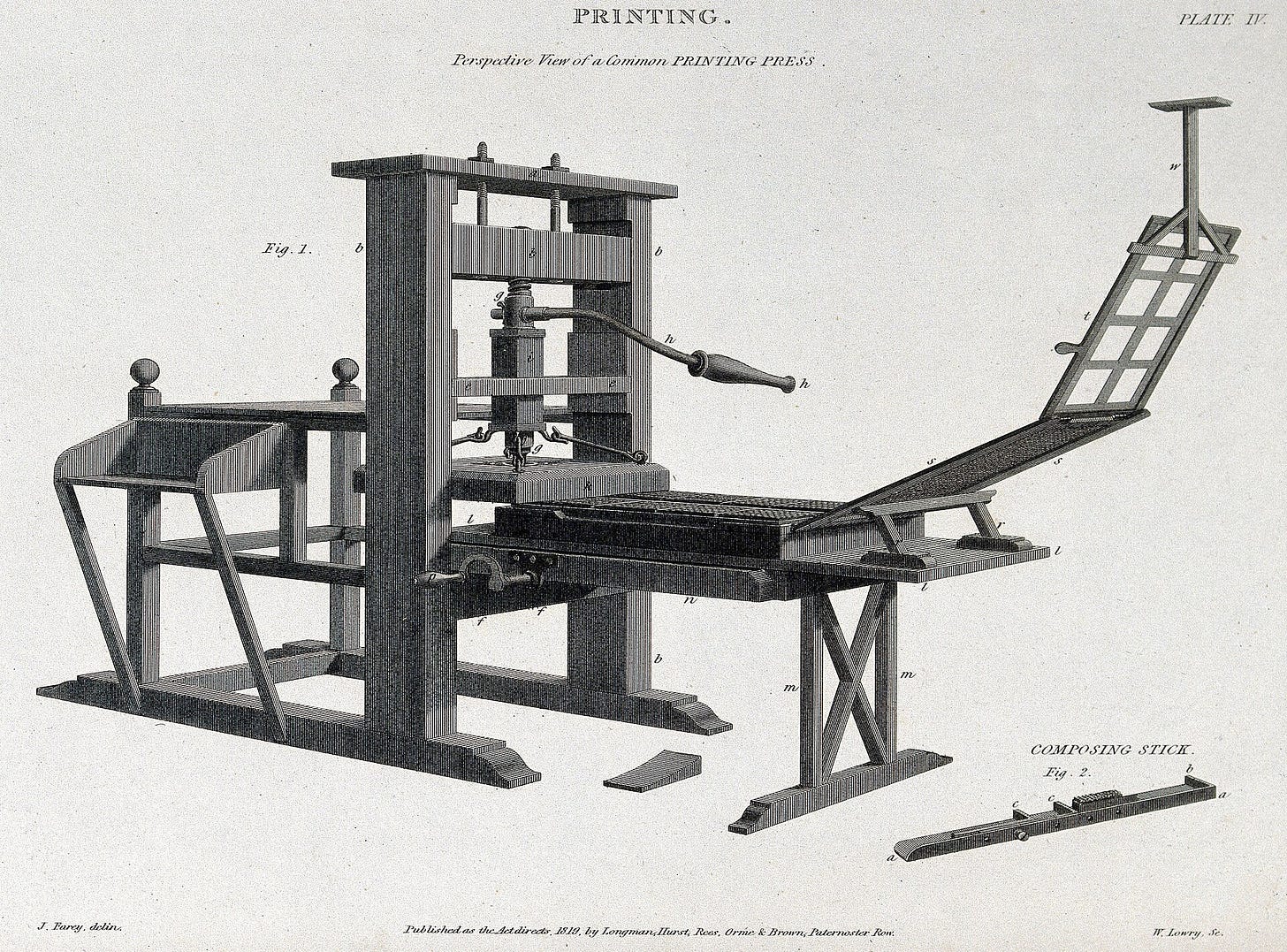

The transformation of printing technology in the Netherlands during the 15th and 16th centuries provides an instructive case study of how the use of an imported technology can lead to significant technological innovation, ultimately resulting in new inventions and applications that advance beyond the original technology.

It is also from this case study that we can start to extract a new hypothesis of competition.

When Gutenberg's movable type printing technology first arrived in the Netherlands from Germany in the 1470s, Dutch printers initially operated as straightforward users of the German innovation. They imported their equipment, materials, and technical knowledge from German sources, and many early Dutch printers had trained in Germany. The initial phase was primarily about technology adoption rather than innovation.

However, as Dutch printers gained experience with the technology, they began making adaptations to suit local needs and conditions. The Dutch book market had different characteristics from the German market - there was a different demand for vernacular texts and commercial documents rather than Latin religious works. This led Dutch printers to experiment with different typefaces and page layouts better suited to Dutch language texts. They also began modifying their presses to handle smaller print runs more efficiently, as the Dutch market often demanded shorter runs of more diverse materials.

Through this process of adaptation, Dutch printers developed several important technical innovations, like:

New methods for casting type that produced sharper, more durable letters

Improved inking techniques that allowed for finer detail printing

Modified press designs that enabled faster operation for small runs

Novel approaches to page composition that facilitated multilingual printing

The competitive commercial environment of Dutch cities played a crucial role in driving innovation. Unlike in Germany, where many early printers enjoyed monopoly rights, Dutch printers operated in a more open market. This competition encouraged them to seek efficiency improvements and develop new products to differentiate themselves. The dense network of trading cities in the Netherlands also facilitated rapid spread of improvements throughout the industry.

By the mid-16th century, Dutch printers had transformed from being merely users of German technology to being significant innovators in their own right. They had developed distinct "Dutch-style" presses that were in some ways superior to German models for certain applications. Some Dutch innovations, such as improved methods for printing illustrations alongside text, represented entirely new capabilities rather than just incremental improvements.

And digging even deeper we find more.

This whole story begins with the introduction of movable type printing from Germany in the 1470s, with the first press in the Netherlands established in Utrech in 1473 by Nicolaus Ketelaer and Gerard de Leempt, likely trained in Germany. Initially, Dutch printers focused on adoption, but they soon adapted to local demands, such as producing books in Dutch, like "Der souter in Dietsche" in 1476. This adaptation led to innovations, particularly in high-quality typefaces and illustrations, with the Netherlands becoming a center for map and atlas production by the mid-16th century. The competitive market, especially in the northern Netherlands, likely encouraged these advancements, contrasting with more monopolistic practices in Germany. By the mid-16th century, Dutch printing techniques and products were influential across Europe, surprising given their initial dependency on German technology.

It's surprising how quickly Dutch printers, starting as users, became innovators, exporting their advanced techniques back to Germany within a century, driven by local market needs and competition.

So, given this - what is our hypothesis? It goes something like this.

(I) Europe can achieve a lasting and robust competitive advantage in technology by focusing on the use and adoption of new technology, driven by a different demand structure, returning talent and an open market tied together by, for example, a dense city network.4

Drawing from the printing press example - these are some of the key components that Europe would have to work with, if it intends to move into this new competitive dimension.

A different demand structure

Let’s start with the different demand structure. The demand for different kinds of applications - books - in the printing press example is interesting, but how does that translate to Europe? As we explore the European demand structure and contrast it to the US one, there is one thing that stands out - and that is the role of public sector procurement.

Public procurement represents twice as large a portion of the IT-market in Europe as it does in the US:

This suggests that if we want Europe to drive the application advantage hypothesis, then using public procurement may well be a key tactic. Using new approaches like innovation procurement, prizes and other ways to build the demand structure for application and use of, for example, AI - will then be key to realize any such advantage.

And it is not just tech procurment, of course. In the EU 14% of GDP is public procurement, compared to around 10 percent for the US - a difference that may not seem much, but which could - if used rightly - give an edge to the EU.

Now, getting public procurement to help and boost innovation in different ways is terribly hard, so this is certainly no simple fix. But the reason we need to focus on this is that it is likely to be a key part of the hypothesis, as the difference in demand here is significant.

There is another difference in demand here as well - one that at first blush looks like a challenge rather than an opportunity.

The European Union has approximately 250,000 public authorities involved in public procurement, including national, regional, and local governments, as well as public bodies like hospitals and universities. In contrast, the United States has an estimated 92,600 entities, including federal agencies (about 1,500), state departments (around 1,000), and local governments (89,925, including counties, cities, and school districts), plus public universities (1,600) and hospitals (1,000). This shows the EU is significantly more fragmented.

This fragmentation is something that the EU both needs to address by pooling resources, and use in order to run experiments on what works. The regulatory instinct to harmonize and force larger scale may not be the right approach here, but the EU may actually want to encourage experimentation and loosen the regulatory frameworks around procurement, especially for innovation procurement overall.

Returning talent

Talent mobility is a key factor in technology competitiveness. Specifically, the returning talent can play an outsized role in building out the capabilities of a country. Asian countries have long been aware of this and have built special returning programs.5

Europe is also aware - but the programs and spending to retain and return talent remain fledgling.6 And it is not entirely clear that just stopping brain drain is the right way to go — the special thing about returning talent is that it seems as if migrating talent increase the productivity of partners back home - so what you want to do is more likely something like designing these talent flows as to really optimize innovation.7

You don’t want people to just stay, nor do you want them to leave permanently. You want them to leave and return. The design of optimal flows here will be a really hard, but very valuable policy problem to work on. Approaches like job placements, support for start ups etc all are worth looking into.8

An open market

The Dutch example emphasized an open market, and this is another thing that the hypothesis - as we formulated it - really needs. This is a subject that requires more in-depth treatment, and laying out here what is needed in the EU to make it a more open market is no simple task.

But there is one thing that is worth thinking through, and that is what open means here, and how different kinds of openness matter. Openness is of course related to trade, competition and general regulation - but an undervalued factor in creating openness is the quality of regulation.

Europe is often accused of burying its companies under red tape - creating too much regulation, but the real problem might be slightly different: maybe it is the quality of the regulation that needs to be addressed?

The European Commission has recognized this for a long time, and has, through different kinds of efforts tried to ensure “better regulation” - but most of those efforts have stalled and been caught in political strife. Yet, there is an opportunity here to ensure that Europe invests in the kind of openness that comes from really good quality regulation. This is also the only kind of regulation that can be used for a regulatory advantage in international trade.

Here there is much to do - not least in defining clear quality characteristics of regulation. We sometimes hear that it is all about how things are implemented in the EU, and that we should not pay such close attention to the regulation itself, but that is a dangerous and deeply flawed argument. The regulation itself should matter.

Mario Draghi’s recent report9 stressed this, but still focused on the idea of administrative burden and cost - but we need much more than that if we want to create truly better regulation: we need a way to determine the quality of the regulation itself, and clear criteria for when to sunset or abandon a regulatory initiative.

This in turn requires defining the success or kill criteria of regulation before it is agreed, and be clear about what regulation is supposed to do. This will not be easy, but it is key to the kind of openness that is needed for the application advantage hypothesis to work.

Take a simple example: under what criteria should the AI-act be abandoned and revoked? Why should the legislators not have answered this question? Clear revocation criteria for legislation that does not work ensures that we do not clog up the system, and also makes for monitoring key metrics - in a way that AI makes possible - in seeking the best, most qualitative regulatory environment we can imagine.

A diffusion game

The application advantage hypothesis is, in many ways, dependent on the diffusion of technology in Europe. For the hypothesis to work, technology needs to spread and be adopted faster in Europe, that is the best way for us to find the right applications and right use cases.

There are many different models of technology diffusion, and the problem is complex. Some argue that technology diffusion follows a fairly rigid schema - and typically takes around 30 years from the launch of the technology to when it actually cuts through - but there are reasons to think that AI could be different, not least because it has the potential to be self-diffusing. What this means is that the technology could instruct others in how it should be used, incentivize use and accelerate it by suggesting uses that may not be immediately obvious.

This, in turn, will also likely accelerate the overall economic benefits, as well as the social change, the technology is ushering in.

From a European perspective, this suggests that one of the key things to do is to build shared experiment infrastructures, where the technology can be tried and tested. As I have argued elsewhere, I believe cities make the best candidates for such “testbeds” - and here Europe has an interesting diversity and range of kinds of cities to draw from.

Densely networked city networks - this was what we saw in the printing press example, and I really don’t think it is that difference in our time and age — but it requires Europe acquires the ability to think in different kinds of resolution. In one sense making Europe competitive requires focusing less on Europe as a cohesive whole, and more on the fractal parts of Europe, city networks and contexts that allow for shorter diffusion patterns and better experimentation.

In conclusion

The application advantage hypothesis - that Europe can build on AI and compete successfully this way - is emerging as a key strategy for a Europe that is finally realizing that it does not need to compete on the same dimension as the US and China. Far from being a consolation prize, this hypothesis is strategically novel and worth exploring in depth. As we do so we need to decompose it into the key policies that will matter now.

I have outlined what I think they are - from looking at differences in demand structure, securing the right talent patterns, opening markets through quality and maximizing diffusion networks - but this is just a start. For any of this to work there is also a need for some political urgency. If Europe is serious about this strategic turn it needs to convene the right institutions to make it work - building links private and public sector that allow for a collaborative reform of Europe’s technological future.

Such a collaborative model could also, in itself, become a competitive advantage in a world where some seem to think that government is increasingly only the problem, and not a legitimate function for solving the eternal problem of how we live together.

And finally, let me address the obvious weakness of using a single example and case study to make the argument here — the reason I wanted to use that was that I have seen it pop up several times and I do think it is interesting as an analogy. To be clear, I do not think that the application advantage hypothesis stands and falls with this case study - but I found it an illustrative story and I am, admittedly, a sucker for stories.

The Dutch printing press transformation is, furthermore, not unique in technological history - similar patterns of adoption-led innovation leadership have emerged repeatedly. Japanese electronics firms in the 1950s-1980s began by licensing American transistor technology but eventually dominated consumer electronics through superior manufacturing and application innovation, creating entirely new product categories like the Walkman. Italian Renaissance banking shows a similar pattern - building upon Arabic and Byzantine financial instruments, Italian city-states developed revolutionary innovations like double-entry bookkeeping and bills of exchange, driven by their dense urban network and competitive markets. The Swedish steel industry of the 18th-19th centuries started with German and Dutch technology but developed superior processes and applications through public-private cooperation, while South Korea's rise in semiconductors followed a similar trajectory - starting by adopting Japanese and American technology but eventually becoming world leaders in memory chips through focused application development and manufacturing excellence.

Even Britain's industrial textile dominance, though perhaps a more complex case, began with the adoption of Dutch and Indian techniques before spawning innovations like the spinning jenny and power loom. These cases share crucial elements: initial focus on adoption rather than fundamental innovation, strong local market demands driving adaptation, dense networks facilitating knowledge spread, competitive local markets, and often successful public-private cooperation.

Thanks for reading!

Nicklas

See Bradshaw, Tim “Europe can still win in AI despite US dominance, says Skype co-founder” Financial Times 2025-01-08 https://www.ft.com/content/89d32399-f773-4bf9-bdaf-e1548aa4acb9

See https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/01/what-leaders-said-about-ai-at-davos-2024/

Theseus, notably, had a mix of approaches including an application-oriented focus on the Mittelstand - SMEs. The THESEUS SME 2009 initiative was a dedicated component of the broader THESEUS research program (2007-2013), receiving €10 million in funding (just 5% of the total €200 million program budget) from the German Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology. The initiative added 12 application-focused projects and brought in 30 new partners, mostly small and medium-sized enterprises. These projects ranged from semantic search platforms for life sciences (GoOn) to intelligent analysis of medical images (RADMINING) and service platforms for mechanical engineering (SERAPHIM). The SME program aimed to facilitate early testing and implementation of THESEUS technologies by smaller companies, with the goal of promoting innovation and competitiveness among German SMEs through rapid technology transfer.

We will come back to this - but there is a point here that we need to stress in the hypothesis: the dense network impacts diffusion.

See Moon, R.J., 2023. Returning talent. The Oxford handbook of higher education in the Asia-Pacific region, pp.451-463.

See for example https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00527-x detailing a 10 million euro program.

See eg Prato, M., 2025. The global race for talent: Brain drain, knowledge transfer, and growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 140(1), pp.165-238. Detailing how remaining collaborators of emigrants become more impactful, file more patents etc as migrants continue collaborations.

See Schmidt, M. (2023). Returning Talent (pp. 451-C21.P81). Oxford University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780192845986.013.21

See https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en#paragraph_47059

Hi Nicklas, this is an interesting and surprising take on the application advantage hypothesis as a competitive Europe strategy. As a signal startups building AI agents in Europe picked up almost half a billion EUR in the first six weeks of 2025 alone.

I liked the Gutenberg example as a classic. The Japanese story is well known and is struggling to renew itself. Thinking of it, even the traditional Norwegian commodity-based industries have an element of the application advantage approach (combined with nature-based advantages): Offshore oil and gas — technology from the US, fish farming — based on development from France and the UK, and even whaling first adopted from the US, then Norwegians combined the weapons with steam engines — almost driving the whales extinct…

Recently, the close-to-complete electrification of mobility, from cars to public transport, to construction work and machinery in the main cities, has for other reasons nearly been a lost case with very little innovation and value creation coming out of it. Except for a few examples of charging technologies, public procurement innovations, and some trailblazing construction sites. This is more due to the low innovation focus in Norway at the moment.

Europe has a natural leading advantage in attractive cities, an outstanding — and the only — history of coping with both democratic models and their inherent revolutions, and historically leading city government models. As application advantage innovation in combination with globally leading public city services, together with renewed “citizen contracts”, could become global role models and “export-article” of public-private innovations.

Thanks.

Thanks for this post! I fully agree that by now, it seems obvious that the old "me too" innovation model where the EU just re-invents what was successful elsewhere has failed. The diffusion model is promising, I think, and on my own Substack, I will publish some thoughts about how such an EU tech policy "flywheel" could look like :-) You also made a good point on regulation: The quality of regulation probably is more relevant than how much regulation we have but I think GDPR is a point in case here: There are many examples where core principles of GDPR are simply not clear even seven years after it came into force and this of course creates uncertainty in businesses that prevent the rapid uptake of new technologies that rely on or work with personal data (and then there's many laws that do not simply have a few gaps but are badly written from the start ...).